DON’T LET POLITICS CAUSE DIVISION; LIFE CONTINUES AFTER ELECTIONS

It is essential to ensure a peaceful election process as we approach January 15th, the election day, because life must go on after the votes are counted. Politics often divides people and fuels hostility. One musician sang: “Tugende tulonde naye tulonde mudembe obululu tebutwawula, Tuve mukuyomba olwabo abesimbyewo obululu tebutwawula,” which means “we all go and vote in peace; votes should not divide us.” This meaningful message emphasizes the importance of citizens participating peacefully in elections, promoting unity over tribal or personal conflicts, and discouraging internal strife. Besides encouraging peaceful voting, it is also important to focus on informed voter participation. Being an educated voter is just as vital as casting a ballot. Voters should take time to learn about the candidates, their platforms, and the potential impact of proposed policies and measures. When people make informed decisions, it strengthens democracy and reduces the chances of manipulation by those seeking to exploit societal divisions for personal gain. It is wise to follow the Electoral Commission's guidelines to ensure a calm election. We all know that elections will produce both winners and losers, as determined by the voters. By following the rules and accepting the authority of the Electoral Commission, citizens can participate in a process that reflects the true will of the people and helps build trust in democratic institutions. Trust in the electoral process is essential to the long-term health of our democracy and encourages more people to participate. Recognizing defeat and congratulating the winner is not a sign of weakness; it shows understanding that there will always be opportunities to run again. In many democracies, graciously conceding is seen as a sign of political maturity. It demonstrates respect for the democratic process and the collective decision-making that elections symbolize. If dissatisfaction with the election results arises, legal options are available for review, provided there is sufficient evidence to justify a recount or annulment, rather than causing disorder that could threaten peace and stability, requiring police to maintain law and order and the military to ensure national security. Ignoring election outcomes can have serious consequences. We are aware that deploying security forces may include using tear gas, rubber bullets, and making arrests. Such actions not only risk personal safety but can also discourage people from voting in future elections, creating a cycle of voter disenfranchisement and disillusionment. It is vital to understand that a peaceful election benefits everyone and sets an example for future elections, showing that respectful dialogue is possible even during disagreements. It is important to face the truth, even if it’s uncomfortable. The military will not remain idle if someone tries to destabilize the country; it must defend the nation, while the police are responsible for maintaining law and order. Our country has experienced enough unrest and conflict recently. We should not reopen that chapter, as it threatens our progress. Promoting peaceful participation today inspires hope for future generations, reminding them of the value of unity and shared responsibility in exercising democratic rights. Furthermore, community efforts to promote dialogue and understanding among different groups can be very beneficial during the election period. Workshops, town hall meetings, and social media campaigns focused on peace and unity can significantly improve the electorate's readiness to engage respectfully with opposing views. Working together to understand one another strengthens our society and helps us move forward as one, prepared to face the realities of democracy. Ultimately, our goal should be to build a culture that values reflection, cooperation, and peaceful transfer of power, creating a brighter, more stable future for all citizens. This election isn’t just an event; it is a pivotal moment that can redefine our national identity, emphasizing cooperation over conflict. conflict. The writer works with the Uganda Media Centre

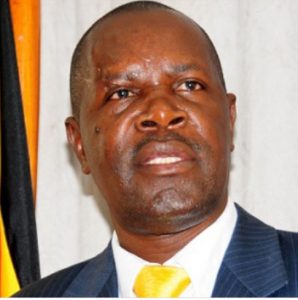

Nanteza Sarah Kyobe